InnerSource is a Lie - A Response to Common Misconceptions

When you search for “InnerSource” on YouTube, one of the first results you’ll likely encounter is a video claiming that “InnerSource is a lie.”

(link: https://youtube.com/shorts/53jEP3mPP3E)

This viewpoint represents a typical pitfall that many people fall into when they first learn about InnerSource.

I want to use this video as a case study to explain what kind of misleading conclusions it promotes. This is a mistake I’ve made in the past as well, and it’s a trap that many people who haven’t deeply explored this field can easily fall into. That’s why I want to examine this with self-reflection and help others find the right path by unraveling these pitfalls.

The First Misconception: “Use React So Others Can Contribute” #

Let me first unpack the argument in this case. The video suggests using React for internal applications “Use React because other people can contribute to it.” This kind of reasoning is rarely heard in actual InnerSource discussions.

should you use react HTMX or solid or something for your company’s internal application now a lot of people what you’re going to hear is use react so other people can contribute to this

This argument can be dissected into three key issues:

- Fundamental misunderstanding of what InnerSource actually means

- Choosing the wrong domain for InnerSource application

- Confusing individual versus team perspectives

What InnerSource Actually Means #

InnerSource is about practicing open source principles within a company. It’s not just about “contributing” or “receiving contributions.”

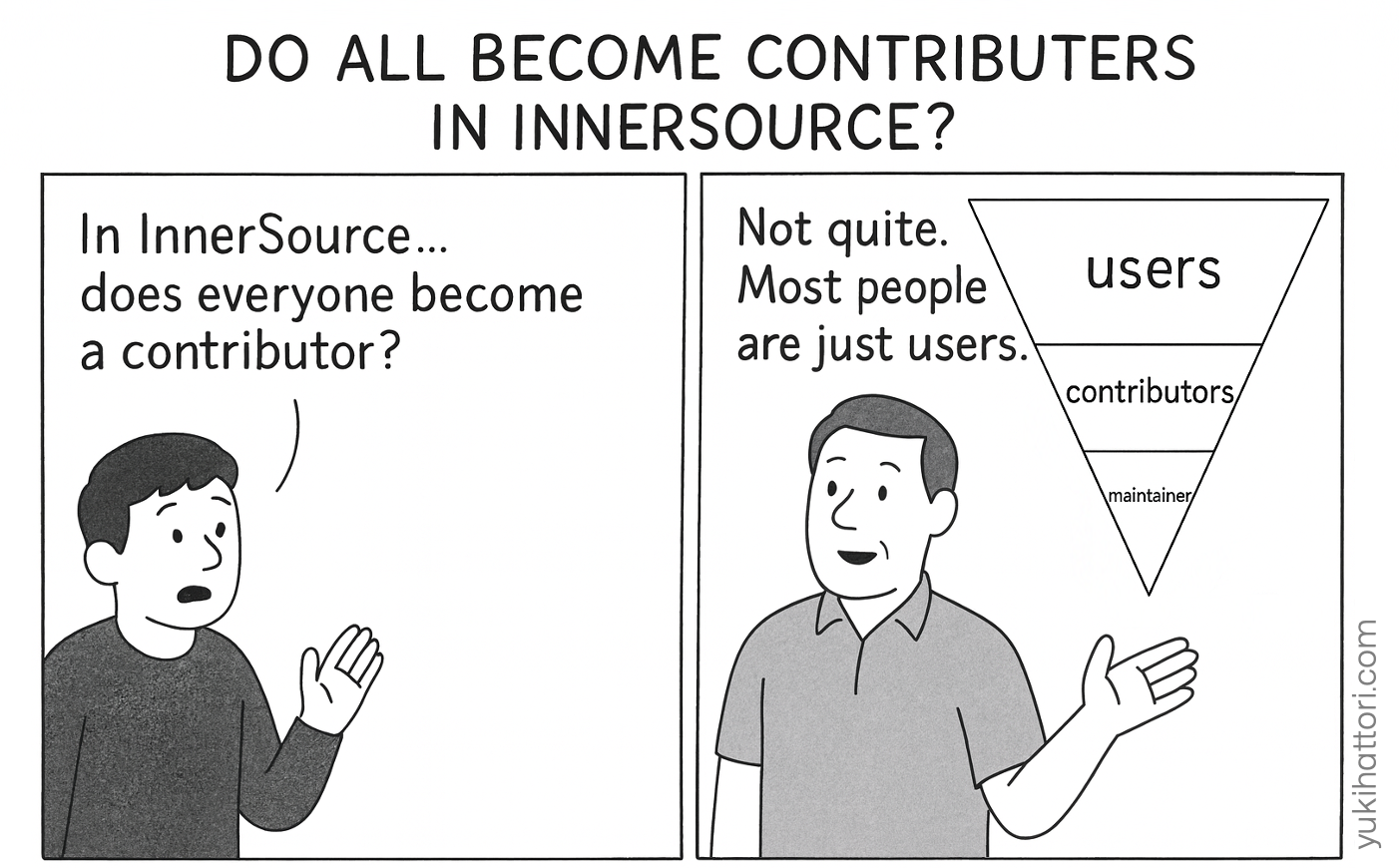

Most people who interact with open source are simply “users.” Some are just consumers, others file bug reports, and only a small fraction actually submit pull requests. InnerSource applies open source learnings internally to create organizations that are open, broadly accessible, with transparent decision-making, and team relationships built on trust through ownership and mentorship. This creates a culture of transparency and collaboration.

This is what “practicing open source internally” means - it’s not just about “receiving pull requests.” Pull requests are merely one result of this culture, not the primary goal.

A Less Optimal Domain for InnerSource Application #

The second issue is that this argument unfolds in a domain where InnerSource and open source face particular challenges.

If you want to “receive pull requests” or “have many people use your code to improve quality,” that might be limited by the nature of your product. It’s clear that sharing “high-dependency components” or platform-level tools would create more value than end-user applications. While stream-aligned teams should still adopt open source practices when beneficial, the collaboration dynamics differ significantly.

In my experience working with enterprise companies, using InnerSource for project-level initiatives where the end users are “non-engineers” presents unique challenges. Why? Because ultimately, these products need to serve the needs of “end users” or “business users” who may lack development skills and direct communication channels with development teams. This creates complex, individualized requirements and longer communication lead times.

InnerSource implementations tend to work relatively well when applied to shared libraries, platform components, development tools, and infrastructure code—areas where the “users” are primarily other developers who can meaningfully contribute to and benefit from collaborative development practices.

While applying InnerSource practices to user-facing applications can bring valuable benefits like transparency and improved issue tracking (which alone makes it worthwhile).

Individual vs. Team Perspective #

The third issue concerns whether “you” refers to an individual or a team.

It’s important to note that InnerSource isn’t necessarily about waiting for someone to contribute to “your personal project” within a company. When InnerSource is applied, there might be cases where people contribute to projects developed during 20% time, like big tech firms, but that’s not necessarily the mainstream approach.

InnerSource is primarily introduced and maintained because it generates ROI through cost reduction, avoiding reinventing the wheel, creating synergies, quality assurance, and removing communication overhead from hierarchical decision-making. This typically involves shared internal libraries, proprietary competitive advantage components, or things with high dependencies that are niche within the enterprise. And these “business benefits” typically flow back to “team operations” in most cases. Ultimately, it’s all about ROI for teams and organizations. If we don’t think about teams, someone will stop you from contributing to projects. You need to justify your ROI whether it’s short-term or long-term.

What’s unique about InnerSource is that it’s fundamentally about team-to-team collaboration. This is where most implementations ultimately end up. It’s not necessarily individuals randomly contributing to convenient personal projects. It’s typically implemented through host team and guest team relationships, where guest teams ride along with parts maintained by host teams. Most enterprises have employees with defined roles and responsibilities, and collaboration tends to happen within these structures.

Therefore, InnerSource is particularly effective when relationships between platform teams and stream-aligned teams (guest teams and host teams) are established. Active co-creation between stream-aligned teams or individuals are more uncertain to succeed naturally.

Criticizing all of InnerSource based on scenarios that are unlikely to work makes no logical sense.

The Second Misconception: “It Never Happens in Real Companies” #

because we want people doing that the reality is that’s not what’s going to happen ever at any company ever inner source

Actually, this is happening. Case studies prove it. Period.

The Third Misconception: “99.69% of InnerSource Projects Will Fail” #

99.69% a lie you’re going to build the entire project by yourself when it goes down people are going to look to you

This might be correct depending on how you define “InnerSource.” As mentioned earlier, InnerSource is not about “receiving PR contributions.”

However, there are three important points to consider:

- InnerSource especially applies to strategic components - it’s not required for all components

- Benefits extend beyond active contributions

- Open source has the same “failure rate” issue

InnerSource is a Corporate Strategy #

When people think about InnerSource, they sometimes imagine radical ideas like “sharing all code within the enterprise” or “everyone contributing to everything.” They might envision hundreds of shared repositories within a company with everyone actively exchanging contributions. Like open source being a strategy for companies, InnerSource is also a corporate strategy with priorities. Companies share “what’s worth sharing” first.

Therefore, the actual number of codebases where code actively flows between teams and vibrant cross-team collaboration occurs is relatively small. This might indeed be single-digit percentages. However, even without active cross-team collaboration, many projects can benefit from being open and transparent. In this sense of InnerSource, enterprises can often share value across many more cases.

While InnerSource includes individual contributions, it is primarily focused on team-to-team collaboration. Therefore, what gets shared through InnerSource tends to be relatively niche within enterprises, or purpose-specific items like forked Linux distributions for particular needs. Or it might simply be open source-like development culture, as when GitHub shares Ruby on Rails code across all employees.

When we condition this percentage discussion on InnerSource that actively collaborates and gets maintained as common requirements, the percentage may indeed be relatively low. However, small collaborations like documentation pull requests or minor configuration changes (sending small patches) between guest teams and platform/host teams happen relatively frequently. When you include these micro-collaborations and transparency benefits that prevent duplicate efforts, these numbers increase significantly.

Open Source Has the Same “Problem” #

On the other hand, if we define it that way, open source would also be a “lie.” Because “99.69% of open source projects will fail.” Most code published as open source doesn’t receive contributions. But nobody says “open source is a lie” because of that. People pursue open source because there are benefits beyond receiving contributions.

Again, “being contributed to” isn’t the only value of InnerSource. And the same holds true for open source value as well

The Real Benefits of Transparency #

Keeping internal code open rather than hidden - at GitHub, architects or solution engineers on the revenue team might be able to examine source code to find relevant information, potentially finding details very close to customer requests, facilitating smoother support conversations, and extracting more accurate information from issues. I live in Tokyo, and sometimes it’s faster to just look at Ruby code to check the implementation, or go to issues to check the background of the changes, rather than waiting for the SF-based product team to wake up to ask implementation questions about the changes and their background.

Using the git blame command, you can identify the “real” stakeholders of the code and ask questions about the background of decisions.

Needless to say, the same applies to other development teams. Having information readily available about components that might create dependencies clearly reduces communication overhead.

InnerSource is about practicing open source principles internally. InnerSource isn’t just about sending pull requests back and forth - it’s about ensuring transparency and gaining benefits through open source-style collaboration. These benefits extend far beyond the few percent of actively maintained repositories to broader cultural implementation benefits.

The Fourth Misconception: “You’ll Get Called Back When You Leave” #

“when you leave the company they’re going to send you a message 6 months later asking you questions or seeing if you would like to contract with them to upgrade your application there is no such thing as innersourcing”

Resources sometimes go unmaintained, but this isn’t an appropriate criticism of InnerSource itself - it’s criticism of failing to implement InnerSource properly. This isn’t criticism of InnerSource, but criticism of lacking maintenance culture where nobody maintains the code. This results from failing to implement InnerSource properly or not considering it at all - the result of lacking ownership.

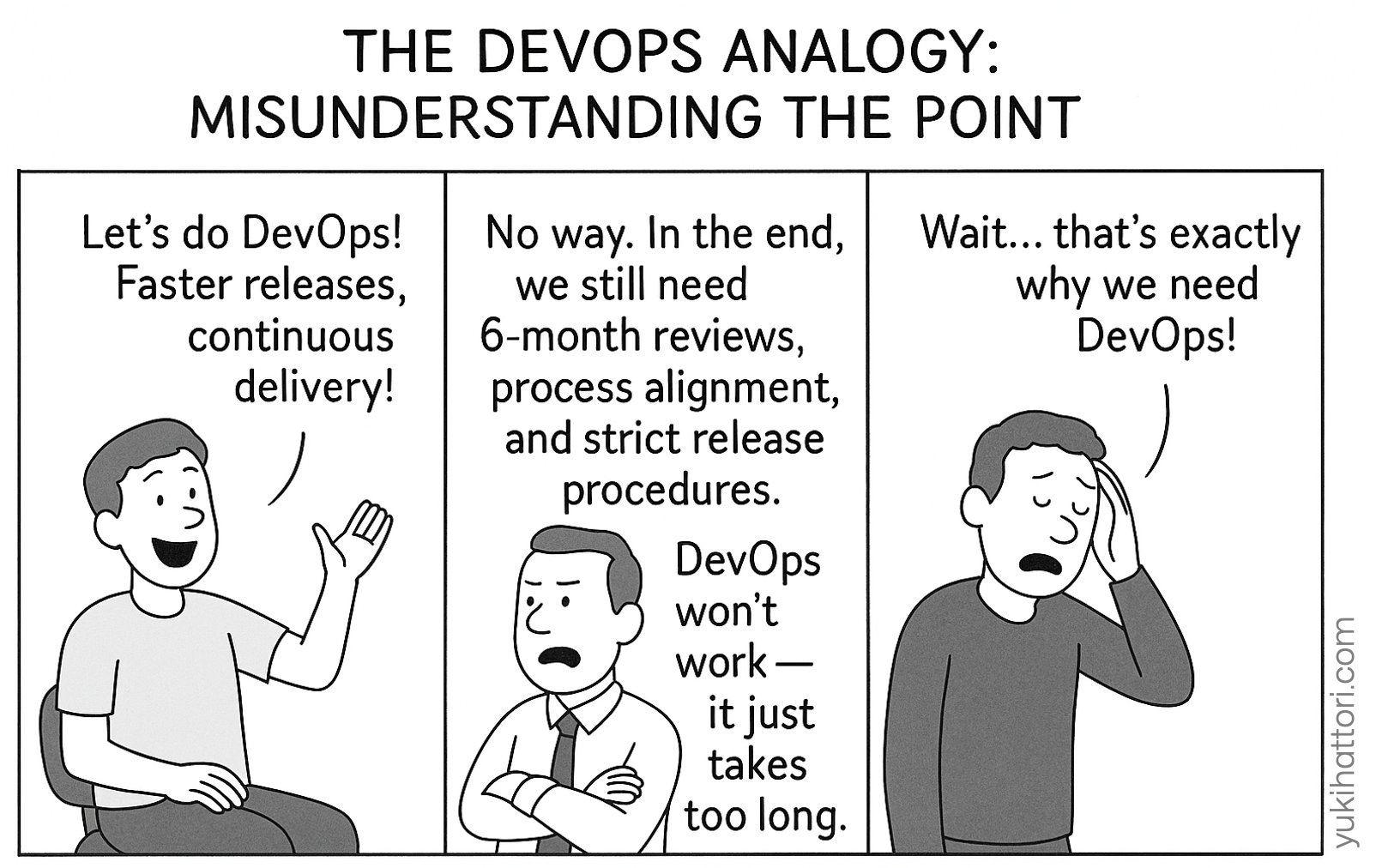

The DevOps Analogy #

This is criticism of failing to do InnerSource, not criticism of InnerSource itself. Sometimes this confuses the logic. To put this in DevOps terms: it’s like saying “companies end up adopting slow review cycles of several months or audits, or adding processes for release decisions, so releases become quarterly or only twice a year. Therefore DevOps, which claims to enable fast releases, is no good.” That’s not because the DevOps methodology is bad, but simply because “there were cases where DevOps couldn’t be implemented.”

Breaking business processes is extremely difficult, and many companies said DevOps was impossible. But even when people thought it was impossible, there were courageous pioneers who worked hard to change the culture and achieved DevOps. The same can happen with InnerSource.

The Fifth Misconception: “You Must Own Everything 100%” #

you own it 100% (which implies: InnerSource where you don’t own 100% is impossible)

“InnerSource means abandoning code ownership” is wrong. InnerSource actually requires teams to own code. This is a common mistake. This is like people who want to abandon maintenance responsibility and say “let’s make it open source.” That doesn’t work.

Individual vs. Team Ownership - Is InnerSource Strong Code Ownership? #

First, is this “You” individual or plural? Though individuals might be listed as CODEOWNERS file in organizations, teams ultimately hold responsibility for code. Contextually, it’s likely talking about Strong Code Ownership. But this isn’t good when considering organizational maintenance. Because employees might quit.

InnerSource is not Strong Code Ownership. At minimum, multiple people need to share responsibility. Having said that, I acknowledge that Strong Code Ownership may emerge in the short term, and in the early stages of a project, strong individual will might naturally lead to such arrangements, but if you want to achieve long-term success, it’s necessary to delegate authority so that the organization can handle maintenance collectively.

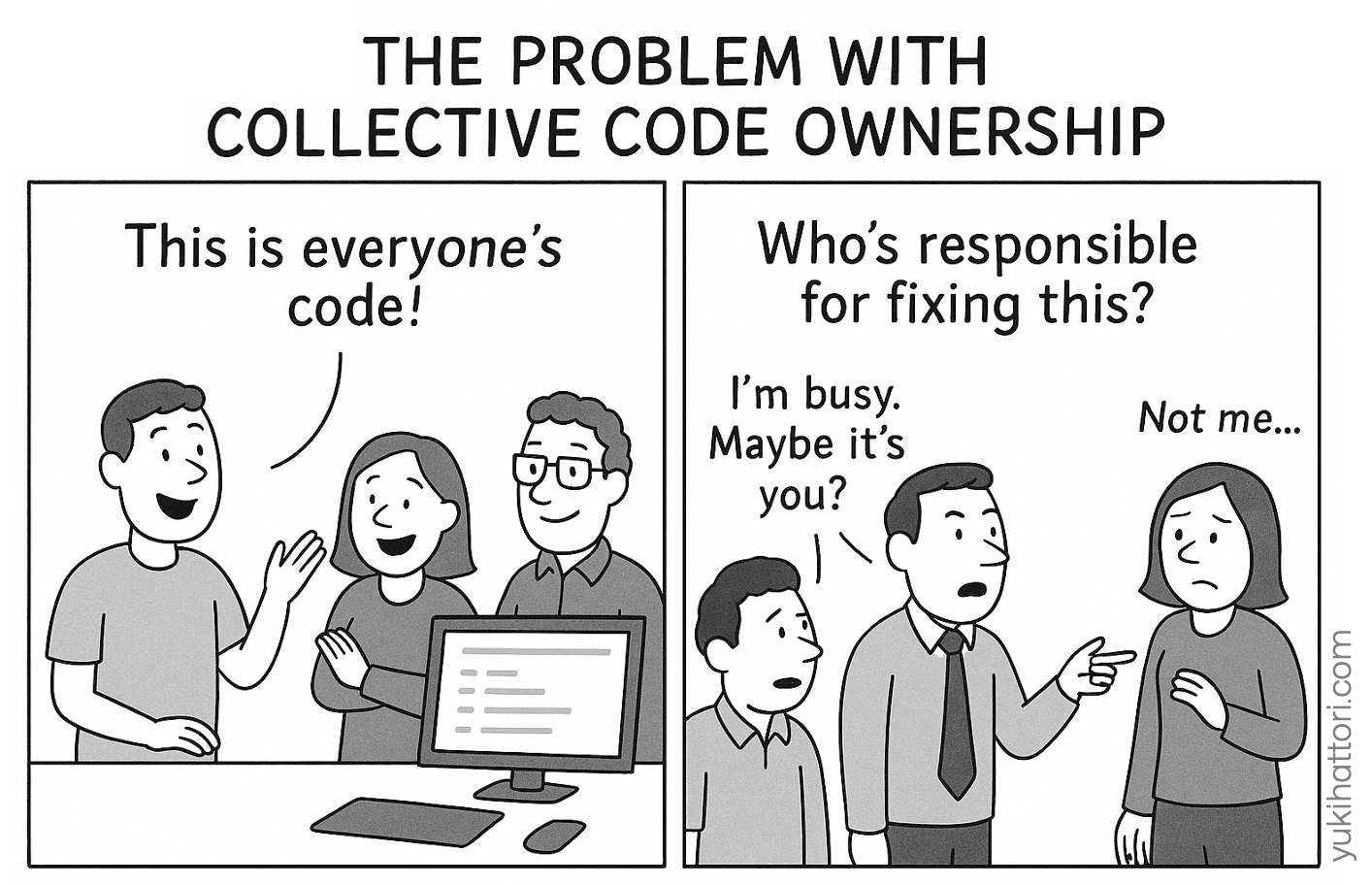

Types of Team Ownership - Is InnerSource Collective Code Ownership? #

This kind of argument might sometimes refer to Collective Ownership. In this case, the argument also seems to suggest that InnerSource means collective ownership, but that’s actually different. InnerSource is not Collective Code Ownership InnerSource involves host teams ultimately handling maintenance. InnerSource is Weak Code Ownership. So while maintenance responsibility is 100% correct, saying “you must own 100% and InnerSource is different” is completely illogical. This is actually an incorrect opinion.

As Martin Fowler famously argued about code ownership, having everyone own code 100% (collective ownership) sometimes creates situations where nobody takes responsibility. That’s very problematic - responsibility becomes unclear and projects ultimately fail.

Weak Code Ownership Model #

In Weak Code Ownership, maintainers exist, host teams maintain projects, and specific parts might bring in trusted committers/maintainers from other teams. Someone might contribute, someone might maintain, but not 100% by “you” or “your team” - it might be quite different. For example, 98% of code might be owned by your team, while 2% might be owned by other teams.

In this case, remember that even if individuals are assigned as code owners in organizations, teams ultimately hold responsibility for code. Teams should own it, and don’t forget this important point.

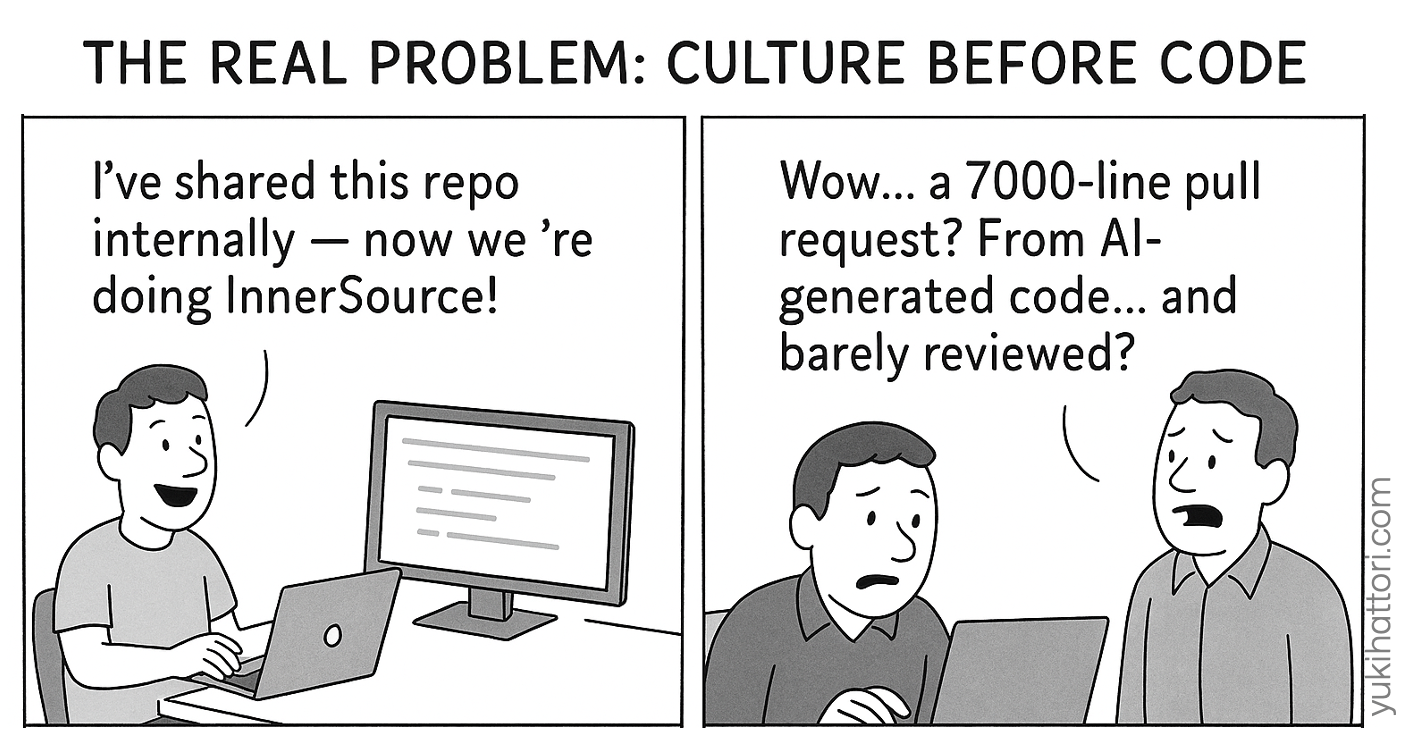

The Sixth Misconception: “Someone Will Drop 7000 Lines on You” #

Every now and then there will be a sufficiently motivated coworker who’s really great and do like a 7,000 line update no explanation but don’t ever fall into this idea that choosing anything for an internal app that you are going to be working on

Having 7000-line pull requests suddenly appear is itself a failure to introduce InnerSource culture - it’s not something that happens by doing InnerSource. This case might worry that introducing InnerSource makes such collaboration happen, but that’s completely wrong.

The Real Problem #

This argument represents failing to implement InnerSource culture and collaborative practices, not InnerSource itself. 7000-line implementations are very limited cases. This represents failure of collaboration culture where 7000 lines get submitted as pull requests suddenly without any notification - the organization should fix this fundamental culture problem, which is pre-InnerSource.

If you want to prevent this, there’s a solution. Foster InnerSource culture within your organization:)

The Reality: What InnerSource Actually Is #

InnerSource is cultural implementation - using open source collaboration practices to enjoy various benefits that open source receives through collaboration. InnerSource’s ultimate purpose isn’t just receiving contributions (pull requests), but includes feature requests through issues, support coordination, and various other benefits, plus transparency in decision-making and practical cultural promotion.

Therefore, I definitively reject the claim that “implementing InnerSource best practices to get pull requests is a lie.”

Understanding Contribution Reality #

“Nobody ever is going to contribute”

In open source collaboration, contributors are indeed a tiny fraction. Out of 1000 users, maybe vast majority are just users, 20 might submit issues or feature requests, 5 might send pull requests, and maybe only one becomes a maintainer.

Again, InnerSource best practices won’t make all 1000 people contribute. InnerSource helps induce such collaboration, but ultimately aims to break down enterprise silos, improve collaboration that’s hindered by traditional organizational constraints, reduce lead times from information silos, and optimize organizational resource allocation using open source practices.

Conclusion #

While the arguments in this case touch on some real challenges, they’re based on common misunderstandings that many people encounter when first learning about InnerSource. These are well-known pitfalls in the community, and it’s understandable how someone might reach these conclusions without deeper exploration of the field.

The key insight is that InnerSource isn’t about forcing open source practices into a rigid framework. Instead, it’s about returning to the fundamental question: what can we learn from open source? By examining open source through a broader lens, we can better adapt these principles internally.

You can join this conversation and bring fresh perspectives. Whether you want to build on this discussion, explore more specific implementation details, or even challenge these arguments entirely - all approaches are welcome. What matters most is maintaining that broad perspective on open source learnings and how they translate to internal organizational contexts.

For comprehensive information about InnerSource, I recommend checking out the InnerSource Commons Foundation. They welcome diverse viewpoints and ongoing dialogue about how open source principles can create value within organizations.